The Lost Art of Crashing the Ruling Class’s Party (and The Real Abundance Bros)

Medieval Baghdad's uninvited guests—and why they might have been onto something.

A break from politics…sort of. I once-again picked up Emily Selove’s Selections from The Art of Party-Crashing in Medieval Iraq at a moment of existential exhaustion. There I was, stuck in the algorithmic churn of doomscrolling, numbly consuming the latest dispatches from our collective collapse, when a book about medieval freeloaders caught my eye. A break from the barrage of bad news, a glimpse into another world. And what a world it was—medieval Baghdad in its golden age, full of cunning tricksters, lavish feasts, and an entire subculture of noblemen who had perfected the art of sneaking into parties they had no business attending.

But the further I read, the less distant it seemed. The tufaylis (loose translation: Party Crashers) of medieval Iraq were not just charming tricksters; they were men who had learned to navigate a world where wealth pooled at the top, where access was a matter of affiliation rather than ability. They were not simply freeloaders—they were survivalists in a system rigged against them, crashing the banquets of an elite that hoarded excess while insisting on its own exclusivity.

Becca Rothfeld, in All Things Are Too Small, argues that modernity has taken on a perverse philosophy of scarcity: at a moment of skyrocketing inequality, we are encouraged by the cultural intelligentsia to accept less, to resign ourselves to deprivation, to treat abundance as an indulgence rather than a right. The tufaylis of medieval Baghdad would have recognized this logic immediately. They understood that systems of privilege depend not just on material hoarding but on the enforcement of artificial limits—who is let in, who is kept out, and who is made to believe they should want less in the first place. Sound familiar? Ours is an age of new gilded barons, where Trump declares himself a monarch and Musk plays the role of his patron or court jester-philosopher. The tufaylis understood something essential about power: that it is built on spectacle, and that entry is often a matter of performance rather than permission. In that sense, their world is not so far from ours after all.

It was, in other words, a book about people who understood how to subvert the system. The tufaylis were neither beggars nor thieves, not quite con artists but certainly not respectable guests. They were opportunists with a revolutionary poet’s sense of timing, men who moved through the city’s most opulent homes with the confidence of those born to excess, despite having none of their own.

Rothfeld critiques the self-imposed smallness of modern life—the idea that to want more, to demand more, is gauche, even immoral. The tufaylis, by contrast, refused to accept this premise. They did not shrink themselves to fit the system; they expanded their reach, inserting themselves into spaces designed to exclude them. Reading about them felt like discovering a missing archetype—somewhere between a grifting conman and the guy who always shows up at brunch with no intention of paying.

The Many Strategies of the Tufayli

Al-Khatib al-Baghdadi, an 11th-century historian and professional collector of gossip, was so fascinated by these freeloaders that he wrote an entire book on them: The Art of Party-Crashing (التطفيل وحكايات الطفيليين وأخبارهم ونوادر كلامهم وأشعارهم). Part satire, part anthropological study, part inadvertent self-help manual for the perpetually underfunded, the book catalogues the many ways in which an enterprising individual might find himself dining at someone else’s expense.

The strategies were varied, each one a miniature masterpiece of audacity. Some relied on sheer verbal agility, reciting a well-placed poem in praise of the host until social convention dictated they be offered a seat. Others worked the long con, embedding themselves in a guest’s entourage like an opportunistic remora, until eventually the host stopped questioning why they were always there. And then there were the true artists of the craft—the men like Bunan, the most legendary tufayli of them all, who turned freeloading into a philosophy.

Bunan’s logic was simple: The host always tells the cook to prepare extra, just in case. I am the just in case. And so he was, slipping into banquets, making himself so integral to the rhythm of the evening that his presence could not be questioned. When confronted, he would deploy an argument so circular and unassailable that it left his accusers too bemused to throw him out:

You ask me in when there’s nothing to eat,

You shut me out when you’re having a feast!

I’d die for you! Could you be any brasher?

Am I not still your party-crasher?

It was, in essence, a spiritual justification for freeloading. God provides for all creatures, Bunan would remind his hosts, and if He has willed that my sustenance comes from your table, who are you to stand in the way of divine decree?

There is something deeply reassuring about the fact that people in the past were just as ridiculous as we are now. If we are to believe the accounts of medieval Baghdad’s own writers, they were drunk, gossipy, full of contradictions, and often found themselves at banquets saying things they immediately regretted. The high courts of the Abbasid era, so often imagined as sites of solemn theological debate and grand poetry recitations, were also places where men debated the finer points of hypocrisy over goblets of wine and where princesses justified their rule-breaking with unimpeachable logic.

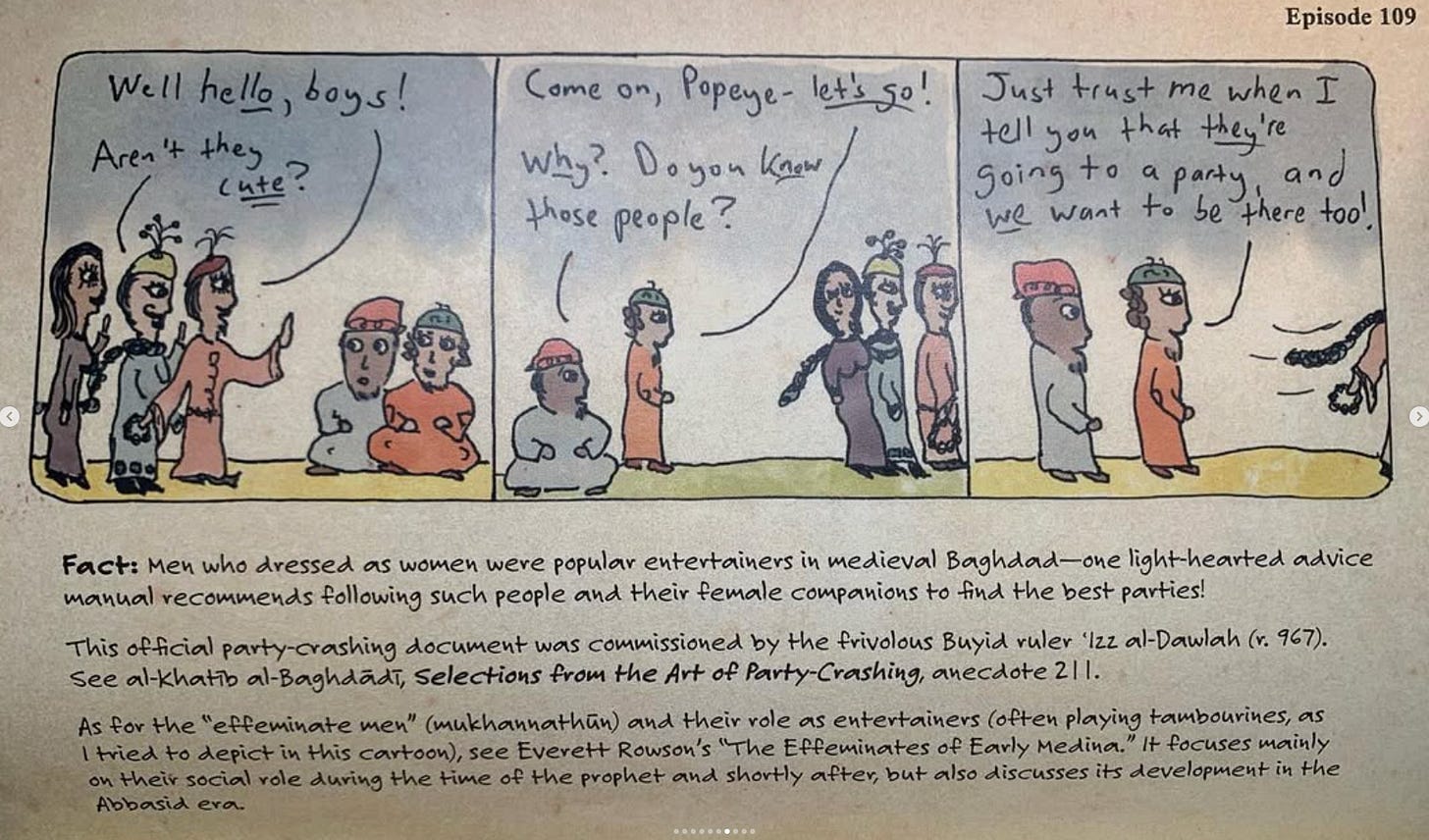

There’s the effeminate party-crashers, or mukhannathūn, a group of cross-dressing men in medieval Baghdad who were so well-attuned to the rhythms of aristocratic nightlife that the 10th-century party manual specifically advised following them if you wanted to find the best parties. “Just trust me,” says one character in the cartoon adaptation of the anecdote, whispering to his reluctant friend. “They’re going to a party, and we want to be there too.” The text does not clarify whether these cross-dressing Iraqis were gender nonconforming by nature, by necessity, or by sheer commitment to the art of revelry, but the historical consensus is clear: they knew how to have a good time.

And then, of course, there is the princess. Ulayya, a poet and royal, is said to have drunk wine only when on her period. “If I am already in a state of ritual impurity,” she reasons, “I may as well go all the way in.” It is, frankly, an unimpeachable argument. There is a particular genius in the logic of the already-compromised. The people who collected and preserved these stories might have believed they were recording moral lessons, but what comes through more strongly is something closer to admiration.

Perhaps the greatest tension running through these stories is the age-old struggle between piety and pleasure. In one scene, a bearded moralist accuses a man of engaging in sinful behavior. The man, reclining with a goblet of wine, does not argue. “I agree,” he says solemnly. “It is sinful. God may be one, but life is complicated.” Then he takes another sip. The lesson here is neither judgment nor approval, but recognition. A concession to the way humans live their lives, caught between what they believe and what they actually do.

The medieval Arabic adab tradition, much like the literature of the Greek symposium, was invested in the kind of storytelling that thrived in dimly lit rooms, over food and drink, among people who had spent just enough time together to lower their guard. These were not just moral tales but social ones, designed to capture the inconsistencies of the human condition—our absurdities, our indulgences, our brilliant justifications for breaking rules.

The Layers of the Tufayli: Trickster, Philosopher, and Mystic

At first glance, the partycrashers were comic figures—their stories full of slapstick reversals, witty rejoinders, and the occasional divine intervention. But as I kept reading, I began to see something deeper in their antics. Tatfil, the art of party-crashing, was not just a way to eat for free; it was a way to challenge the very structures of power that dictated who deserved to be at the table in the first place.

Take, for example, the story of Al-Jahdami, a scholar in 9th-century Iraq, who was constantly invited to the best parties. His neighbor, aware of this, simply followed him everywhere, assuming (correctly) that no one would dare question his presence. When Al-Jahdami finally tried to expose him, invoking the Prophet Muhammad’s disapproval of party-crashers, the neighbor fired back with a different hadith: Food for one is enough for two, and food for two is enough for four, and food for four is enough for eight. With this, the host had no choice but to let him stay.

It was, in its own way, a critique of exclusivity, a reminder that abundance is meant to be shared. In a world that tells us there is not enough to go around, the tufayli operates on the assumption that there is more than enough—if you are bold enough to take it.

At its most mystical, tatfil even takes on a spiritual dimension. In some tales, the tufayli resembles a critique of a wandering Sufi mystic, someone who embraces poverty yet always finds his way into the best feasts. One poem mocks the ability of a certain Sufi to divine where the best food will be served:

If deep beneath the Byzantinian soil

Pots are hot or dinner’s on the boil,

You, from China, quickly come a-riding…

You always could divine where pots are hiding!

These men were seen as both parasites and prophets, figures who blurred the line between scoundrel and sage. Their presence at a feast was both an annoyance and a reminder: that the world does not belong only to those who can afford to buy their way in, that wit and audacity are currencies of their own, and that sometimes the best seat at the table is the one you take for yourself.

In Defense of a Certain Kind of Party-Crashing

Maybe, in the end, we need more tufaylis. Not the kind who hoard power and privilege, but the ones who remind us that doors should be open, that abundance should be shared, that an extra chair can always be pulled up to the table. The ones who challenge the arbitrary rules of exclusivity and ask, Who says you belong here more than I do?

The tufayli would find something depressingly familiar in Rothfeld’s diagnosis of contemporary scarcity. Rothfeld argues that modernity has taken on a philosophy of meagerness, a self-imposed minimalism where we are trained to expect less, want less, and accept that the pleasures of abundance—whether in art, love, or the right to linger at a banquet—are indulgences rather than necessities. The tufaylis knew better. They crashed feasts not just for food but as a quiet act of defiance, an insistence that wealth should spill over rather than congeal in the hands of the few. Like Rothfeld’s critique of simplicity, their antics reveal the ideological sleight-of-hand that calls excess a vice only when it trickles downward. If abundance is good enough for patrons and kings, why shouldn’t it be good enough for the uninvited?

Rothfeld skewers the modern obsession with smallness as a kind of asceticism masquerading as virtue. The decluttering movement, she argues, reduces life to a series of stripped-down functional objects, as if a person could be made freer by owning only what they "need." The tufayli understands that need is an elastic category, that what we require to survive and what we require to live fully are not the same. In this sense, the freeloading poets and scholars of medieval Iraq were not merely party-crashers but prophets of a more generous world. They rejected the idea that scarcity was a moral necessity. Instead, they performed a different kind of radical minimalism—not the renunciation of things, but the renunciation of exclusion itself. Their very presence at the feast was a critique, an insistence that luxury should be shared, that the spectacle of power can be infiltrated, subverted, and, if done with enough charm, even co-opted.

Both Rothfeld and the tufaylis diagnose an economy of artificial limits, where deprivation is not just tolerated but aestheticized. The contemporary declutterer, who purges her possessions in the name of "serenity," is not so different from the political economist who insists that we must tighten our belts while billionaires play at space colonization. The tufaylis expose this logic as performance, revealing that the feast is always prepared with surplus in mind—only the guests are kept out. In an era where millionaires host TED Talks on minimalism while hoarding obscene wealth, maybe we need more Bunan-style party-crashers, declaring, I am the just in case, and sitting down at the table before anyone can think to stop them.

After all, isn’t that what the new kings and patrons of our techno-feudal age fear most? That someone, unvetted and uninvited, might expose the fact that their palaces are not fortresses but stage sets, their grandeur not a divine right but a carefully curated illusion? That the boundaries they have built—between wealth and poverty, access and exclusion, the deserving and the unworthy—might be nothing more than theater? The tufaylis of medieval Baghdad understood this instinctively, and perhaps, in an era where billionaires cosplay as emperors, we should too.

And if all else fails, take a note from Bunan: walk in with confidence, grab a plate, and declare, I am the just in case!

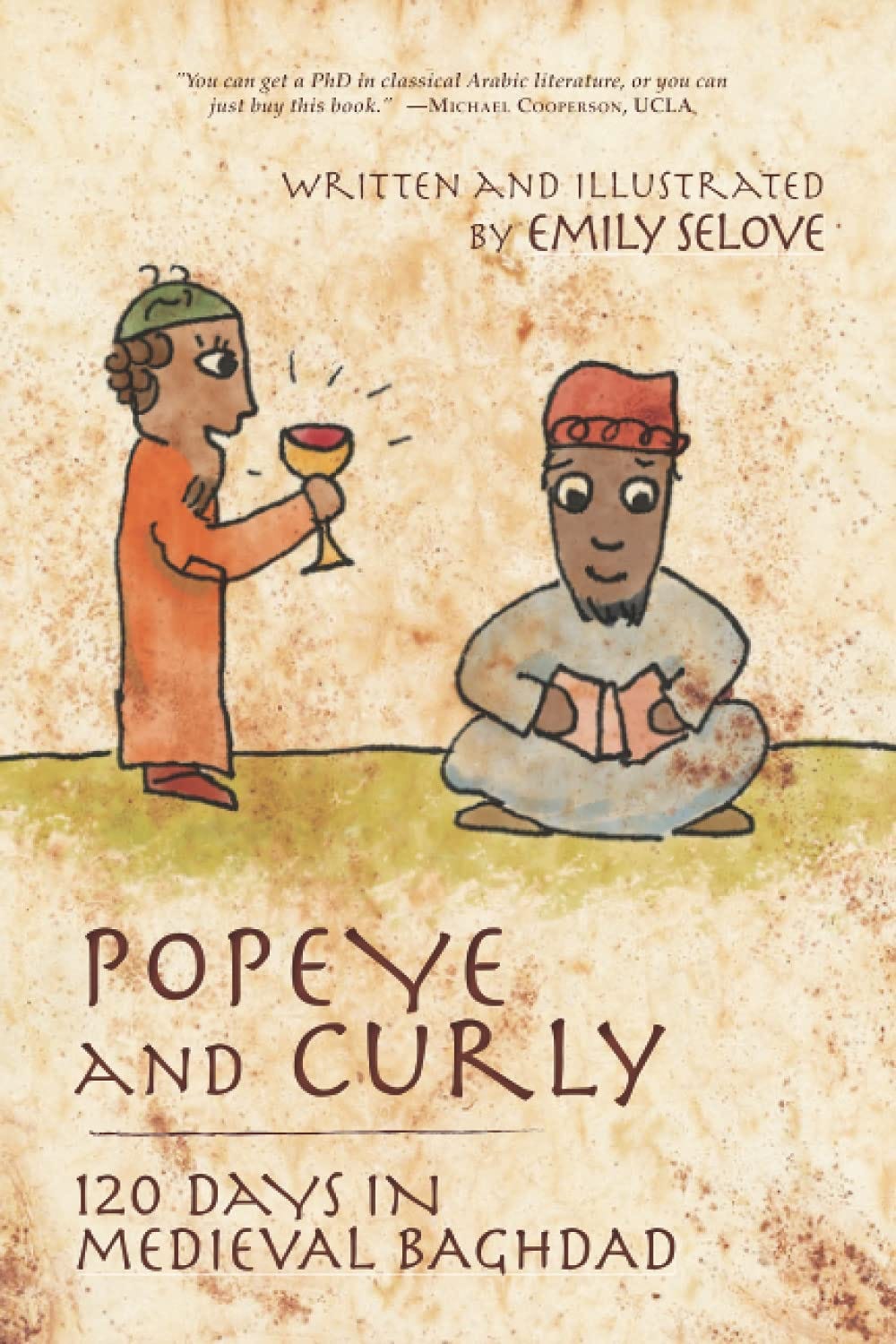

![Selections from The Art of Party Crashing in Medieval Iraq [Book] Selections from The Art of Party Crashing in Medieval Iraq [Book]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F7c9cc589-8ec9-4514-810f-2404003894f5_900x1227.jpeg)

“They crashed feasts not just for food but as a quiet act of defiance, an insistence that wealth should spill over rather than congeal in the hands of the few.” Thank you.

Very interesting thoughts!!!