Liberal Philanthropy’s Misguided Quest for “Joe Rogan of the Left”

Until progressives treat media as movement infrastructure, it’ll keep losing the war for attention.

A recent Media Matters study confirmed what many have long suspected: right-wing media has thoroughly colonized the digital entertainment ecosystem. Whether it’s comedy, sports, or long-form podcasts, conservative voices dominate. Nine of the ten most-followed online shows lean right, with figures like Joe Rogan, Theo Von, and Charlie Kirk commanding audiences that dwarf their progressive counterparts. The right isn’t just winning the media war—it’s setting the terrain of politics through it.

The liberal response to this dominance has been, frankly, unserious. Rather than building a robust, independent, and ideologically coherent media infrastructure, Democratic-aligned institutions and progressive philanthropy have defaulted to a strange overcorrection: either (1) investing in entertainment that only lightly brushes against politics, hoping progressive values seep in through cultural osmosis, or (2) funding party-sanctioned messaging that reinforces Democratic orthodoxy, without grappling with the anti-establishment and populist appeal that gives right-wing media its edge.

Both approaches are failing because both fundamentally misunderstand how the right actually wields media power.

Conservative media isn’t just successful because it’s entertaining. It’s successful because it is a parallel political infrastructure—one that fuses ideology, entertainment, donor money and mobilization into a self-reinforcing loop.

Right-wing media does not react to the Republican Party; it defines it. Figures like Ben Shapiro and Charlie Kirk don’t wait for RNC talking points—they create them. They shape the conservative worldview from the outside in, disciplining elected Republicans through relentless pressure while radicalizing audiences against mainstream institutions.

Progressive media, by contrast, remains trapped in a reactive, defensive posture, often litigating GOP narratives rather than setting its own. And unlike its conservative counterpart, it is too often tethered to party elites, hesitant to challenge institutional Democratic power, and still operating as if gatekeepers hold the same influence they did 30 years ago.

Unlike their right-wing counterparts, most political content creators on the center-left and left operate as independent freelancers, without institutional backing, full-time salaries, or basic benefits like healthcare. Many juggle multiple income streams—subscriptions, ad revenue, crowdfunding—just to sustain their work, leaving them vulnerable to burnout and reactive rather than strategic in their output. They often work alone, without the support of editors, researchers, or political operatives who could sharpen their messaging and deepen their impact.

In contrast, right-wing content creators are frequently embedded within a well-funded ecosystem, backed by think tanks, billionaire donors, and political organizations that provide research, staff, and media connections. The result? Right-wing media functions as an ideological machine, while left-wing content creation remains scattered, precarious, and too often detached from the movements and institutions that could amplify its reach.

This is the real asymmetry: the right’s media ecosystem is unabashedly ideological, intentionally insurgent, and generously resourced. The left’s remains reactive, scattered, and deferential to the Democratic Party. Until that changes, the left will continue losing the battle for public opinion—one podcast, one news cycle, one election at a time.

The Liberal Fantasy: Entertainment as Politics and the Limits of DNC Cheerleading

At the heart of the progressive media dilemma is both a category problem and a scope problem. Many right-wing creators have found success by labeling their content as “comedy” or “culture”—even when that’s a stretch—and eagerly diving into the world of pop culture, celebrity gossip, and viral controversies. The left, by contrast, often treats these realms as unserious or beneath them, despite their enormous influence on low-information and swing voters. While figures like Canadce Owens, Andrew Schultz, and Ben Shapiro use The Barbie Movie or the Blake Lively/Justin Baldoni discourse to subtly reframe the #MeToo movement—as Taylor Lorenz has noted—progressive media often cedes this terrain entirely. Entertainment and celebrity news are still viewed by many liberal commentators as frivolous, rather than as battlegrounds where public values are shaped and political narratives are tested.

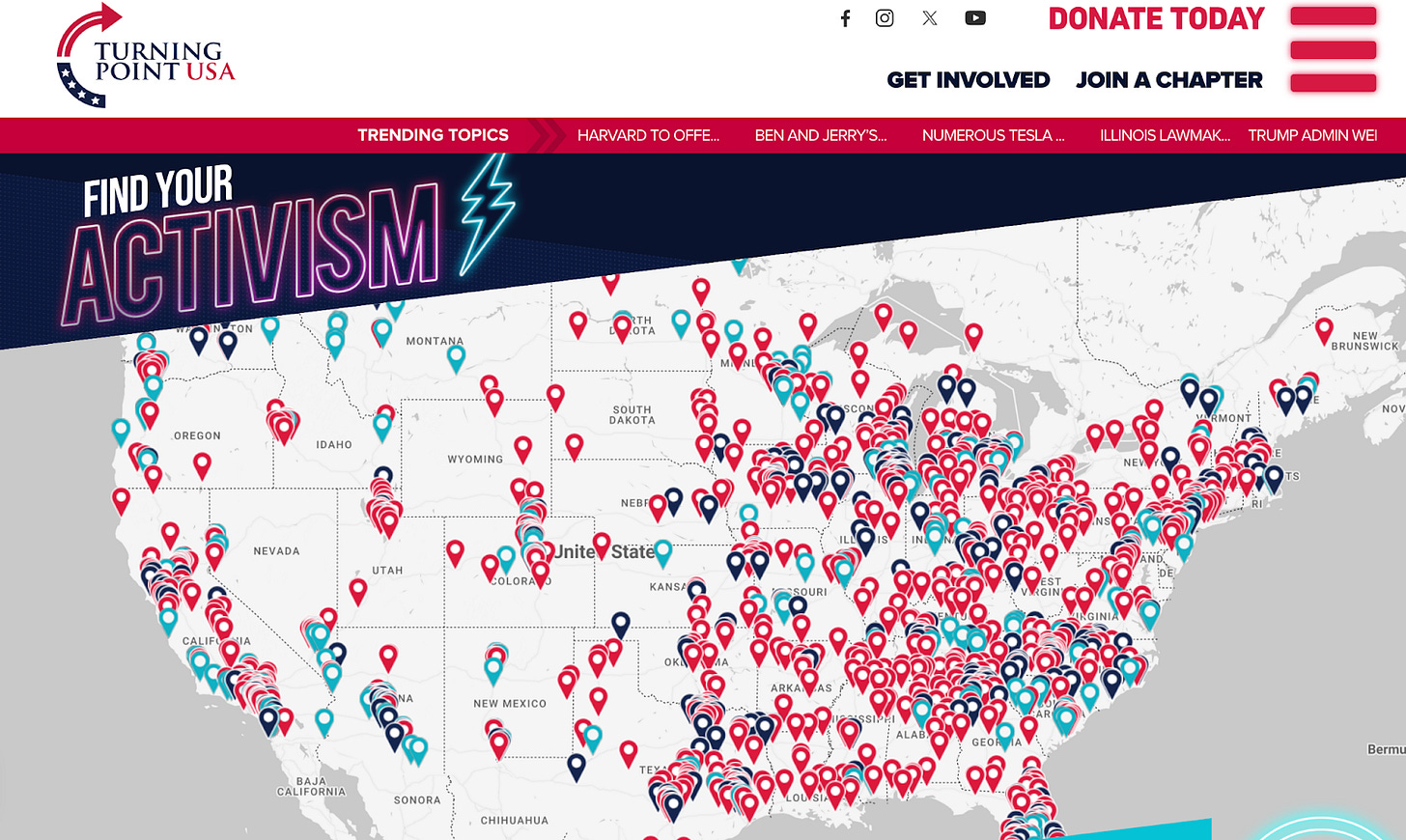

To be sure, the left needs to engage in pop culture, needs humor and needs to be entertaining. But right-wing media is also powerful because it is structured as an ideological project, not a content strategy. The Daily Wire doesn’t just churn out Ben Shapiro clips; it funds a network of movies, children’s programming, and scripted shows designed to socialize an entire worldview. Turning Point USA isn’t just a content organization—it’s a sophisticated political machine that mobilizes audiences while generating viral, outrage-driven content to sustain engagement. These institutions aren’t just chasing clicks; they are constructing a durable, parallel media ecosystem that fuels political outcomes.

On the other side of the spectrum, the other major miscalculation is treating the media as an extension of the Democratic Party rather than as an independent power center. Too many progressive media projects function as de facto DNC surrogates, producing content that reinforces existing Democratic narratives rather than shaping them. But partisan loyalty is not a strategy. The most effective media movements in history—from abolitionist newspapers to early 20th century socialist pamphleteers to mid-century conservative radio—were first aligned with political movements, not specific party institutions.

Conservative media doesn’t spend its time defending the GOP establishment—it pressures it and drags it toward action. Progressive media, by contrast, too often acts as a shield for Democratic elites, reluctant to criticize party leadership, unwilling to push a genuinely insurgent political line, and too focused on defending politicians rather than worldviews. The result? A media infrastructure that is neither truly oppositional to conservative hegemony nor capable of reshaping the ideological boundaries of politics itself.

The Case Studies: Exceptions, Not the Rule

There are bright spots. The Majority Report, Zeteo, and Hasan Piker all represent attempts to build serious progressive media platforms that go beyond traditional electoral cheerleading. But their impact remains limited—not because they lack influence, but because there is no larger institutional infrastructure sustaining and expanding their work.

Hasan Piker has built one of the largest left-leaning digital audiences, particularly among younger, online-first viewers. His success is not just in raw numbers but in his ability to translate complex political issues into accessible, engaging narratives. But Hasan is just one person—without a broader network of progressive creators, his influence remains isolated.

The Majority Report with Sam Seder does serious left political analysis, but is constricted as a small team and largely preaches to the already-converted. It excels at breaking down conservative arguments but is not deeply embedded in the politics of Washington or the ins-and-outs of social movement campaigns.

Roland Martin has developed an impressive independent Black media platform with Roland Martin Unfiltered, aiming to fill the gaps left by legacy media. While Martin’s show brings essential coverage to racial justice issues and Black political power, its reach remains constrained by the broader lack of investment in center-left Black media infrastructure. Unlike conservative media ecosystems that elevate and sustain figures like Candace Owens or Ben Shapiro, Black media remains fragmented, with little institutional backing to expand its influence.

Crooked Media’s Pod Save America has built one of the most successful center-left media enterprises of the past decade, proving there’s a massive audience for sharp, engaging liberal political content, particularly for college-educated liberals in their 30s-40s. Their greatest strength—and weakness—is their insider status. They’ve built an impressive mobilization machine, directing listeners toward voter outreach and fundraising with unmatched efficiency. Their viewers are core Democratic Party voters and volunteers. But their approach leans more toward Beltway middle-class realism than a working-class populist insurgency.

Mehdi Hasan’s Zeteo is a rare success story of a progressive media project that operates independently of corporate, philanthrophic, or Democratic Party constraints. In just four months, Zeteo has amassed over 31,000 paid subscribers and $3 million in annual revenue—proving that a serious, aggressive progressive media project can be financially viable. But one Zeteo is not enough. We need an entire progressive media ecosystem—not just individual success stories.

What’s missing is a coherent, structural approach to progressive media investment. With some notable exceptions—including promising new efforts by Jen Ancona, Glennis Meagher, and Amelia Montooth—most of the left lacks the long-term strategy that conservatives have embraced for years. Right-wing billionaires have built and funded a vast network of ideological media institutions because they understand a fundamental truth: control over content and information is a form of political power.

Clearer Roles, Playing to Strengths

Our current media ecosystem could be strengthened by clearer division of labor. For example, with philanthropic backing, non-profit directors are trying their hand at YouTube shows, TikToks and podcasts. Often, the content is strong and the production value high. And yet, the channels struggle to ever break even subscribers, let alone viewers, in the four-digits. That’s not a reflection on their talent—it’s a reflection of how hard it is to break through in digital media. It takes years to build a meaningful subscriber base. YouTube favors algorithms, scale and oh yeah, the right. Becoming visible on the platform often requires functioning more like a media company than a political project.

Additionally, non-profit directors and organizers are already stretched thin. They shouldn’t be asked to become YouTubers, graphic designers, and audience development strategists. Instead of fragmenting efforts into dozens of small channels, we need shared media infrastructure that exists above and beyond any single organization or personality. The goal isn’t to have everyone start their own show; it’s to ensure the right voices, messages, and stories reach mass audiences through the platforms where people already are.

Another example - while the independent media ecosystem has grown increasingly robust, with ideologically aligned outlets like Mother Jones, Jacobin, Media Matters, Democracy Now!, and The Nation commanding loyal audiences and meaningful reach, many of these platforms remain faceless. They are strong on content but weak on character. What’s missing is personality-driven media: hosts, creators, and storytellers who build parasocial relationships, drive engagement, and shape political identity.

This is a major opportunity. These outlets have audience, capital, and brand recognition. But they haven’t built a bench of faces, populist voices, and compelling characters who can break through in the attention economy. It’s not just about reporting—it’s about recognition.

In short, it’s time to stop reinventing the wheel and start building the megaphone.

Who Are We Trying to Reach?

If progressive media is going to compete, it also needs to be clearer about its target audiences. Right now, too much left-leaning content is misaligned with the people it actually needs to reach. The core constituencies for different lanes of a revitalized progressive media ecosystem should be:

Democratic Primary Voters – The voters who shape the Democratic Party’s agenda—young liberals, college-educated whites, and older Black and Latino voters—are still deeply influenced by legacy and elite media. Outlets like The New York Times, CNN, and MSNBC don’t just reflect the party’s center of gravity; they help define it—forcing progressives to fight a two-front war: persuading institutional gatekeepers while also trying to build alternative platforms that can compete for attention. The right, by contrast, long ago abandoned this model for self-contained echo chambers—and is winning because of it.

Volunteers, Activists and Organizers – Volunteers and activists in groups like Indivisible, DSA, and MoveOn, or stalwart followers of electeds like AOC, Chris Murphy, Jasmine Crockett, and Bernie, have more time for politics than the average person, but commitment to a person or organization is not the same as commitment to a worldview. The right’s media doesn’t just inform—it excites, indoctrinates, disciplines, and mobilizes, ensuring its base moves with ideological clarity and strategic focus. A stronger progressive media ecosystem could do the same by giving those already involved some ideological support and reinforcement.

Low-Information Voters – They aren’t tuning into MSNBC or refreshing political news—they’re consuming entertainment, culture, and personalities they trust. They’re skeptical of institutions but drawn to populist, anti-elite narratives, especially when delivered through charismatic, outsider figures. If the left doesn’t reach them through culture and compelling voices, the right will.

The “Alt-Left” Misinformation Pipeline – Some figures exploit left-wing aesthetics to launder bad strategy and misinformation. Their influence is growing, and progressive media must compete for these audiences directly rather than ceding them to conspiracy-driven nihilism.

The Left Needs to Build Power, Not Just Content

The lesson of right-wing media dominance isn’t that progressives need “a Joe Rogan.” It’s that the left needs its own ideological infrastructure—permanent, expansive, and independent of Democratic Party control that can build and represent working class populism.

Until progressives recognize this, they will remain trapped in a cycle of reactive, defensive, and ultimately ineffective media engagement. The right has already built its machine. If the left doesn’t catch up, it will keep losing—not just in elections, but in the deeper contest over who defines political reality itself.

Waleed Shahid is the director of The Bloc and a political strategist.

Francesca Fiorentini is a journalist, comedian, and commentator known for her sharp analysis and satirical take on politics. She hosts The Bitchuation Room podcast and runs a popular YouTube channel with over 148,000 subscribers, where she breaks down current events with humor and insight.

"This is the real asymmetry: the right’s media ecosystem is unabashedly ideological, intentionally insurgent, and generously resourced. The left’s remains reactive, scattered, and deferential to the Democratic Party." Scattered and thus underfunded is the most important left media characteristic. I identify with this post. I have been writing about the need to coalesce the Substack posters into one or more media powers. The Upgrade to paid button on this post is an example of the demand for funding from too many vertices of the left polygon. The examples of leftist media in this post were helpful. Notably, even though I have searched repeatedly, I only had identified Zeteo among the examples. The others are media strangers to me. I would add the Lincoln Project particularly the posts by Steve Schmidt.

Hmmm... no mention of:

- Meidas Touch - 4.5 million YouTube subscribers. And is now getting more podcast listeners than Rogan.

- Brian Tyler Cohen - 4.1m YT. Has interviewed many Dem politicians - including Joe Biden. Has a Podcast. And is author of the book "Shameless".

- The Bulwark - 1.1m YT. Has great contributors, including Tim Miller, JVL, Sam Stein & Sarah Longwell.