The following is authored by Waleed Shahid and Jee Kim (bio at end of piece).

Introduction

Two months ago, the Populist Manifesto struck a chord in progressive circles, capturing frustrations simmering within the Democratic Party: a slide toward elite cultural politics, an increasing detachment from working-class concerns, and an inability to build the broad, majoritarian coalitions needed to confront the ascendant far right. The 2024 election results and steady drumbeat of post mortems have since deepened this discussion, underscoring the need for a more candid reckoning with the party’s strategic missteps and the entrenched structural forces shaping today’s political landscape.

This piece builds on that foundation (TLDR version can be found here), first digging into greater detail of what a realignment would entail and then closing by addressing a critical question: How do we move from diagnosis to action? It integrates lessons from the recent election while situating them in a broader, historical context of political realignments, and our current media reality. Our collective goal is clear: to craft a progressive populism capable of winning, not just in the next election cycle but for the long term. And our long term objective requires the transformation of the Democratic Party.

What will realignment take?

Most discussions of realignment center on the makeup of a party’s base – whether in primaries or general elections – an important but often oversimplified distinction, while overlooking the myriad of other factors that shape who enters, exits, and wields influence within a coalition. We dig into some of these considerations below.

Who does the Democratic Party represent?

As many have noted, the Democratic Party’s increasing dependence on college-educated voters has come at a steep cost, as it continues to bleed support among non-college-educated voters. What’s even more alarming is the historic rate of decline among non-college-educated voters of color in 2024, a demographic that has long anchored the party’s base. This isn’t just about shifting numbers; it’s about the party’s inability to connect to the economic and social aspirations of working-class communities.

This shift isn’t inevitable; it’s the result of strategic decisions, or more often, the absence of them. The Democratic Party has treated its coalition as static, taking for granted the loyalty of key demographics while failing to reckon with the disaffection growing among working-class voters. In doing so, it has allowed itself to be increasingly influenced by the affective and policy preferences of the upper-middle class, where moral signaling often overshadows concrete, material concerns.

Consider the role of the “professional-managerial class” (PMC) in shaping Democratic politics over the last half century. Coined in 1977 by Barbara and John Ehrenreich, the PMC consists of the burgeoning class of college-educated white collar professional and managerial workers whose influence over our politics has grown drastically. In the right-wing populist imagination, the PMC is a key villain of our time: a class of technocrats, middle management, and cultural arbiters whose priorities are disconnected from the lives of ordinary Americans. The backlash against the PMC and the institutions they manage reached new heights during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The PMC poses a unique challenge for Democrats and progressives. While this group embodies values like expertise, institutional stewardship, and public service, it is increasingly viewed as a symbol of elitism and status quo. Whether fair or exaggerated, the perception that Democrats cater more to the preferences of affluent professionals than to the material needs of working people has fueled a populist backlash on both the left and the right. The influence of the PMC not just in the Democratic Party but in social movement organizations also contributes to the insularity and blindspots that were put on full display in November.

What does the Democratic Party represent?

To rebuild, Democrats must go deeper than patching a fractured coalition. They must articulate a populist economic vision that centers on the cost of living struggles of working people, a vision so compelling that it renders the far-right’s divide-and-conquer culture wars impotent and irrelevant. They must advance a multiracial democracy bold enough to challenge the unchecked power of tech oligarchs, viscerally and visibly punishing corporate greed while loudly redistributing wealth and power.

The message from exit polls and focus groups is stark: non-college-educated voters across racial lines expressed frustration with a party that seemed more invested in defending Biden’s electability, justifying its inaction on cost-of-living issues, or engaging in elite cultural debates than tackling the problems that dominate their lives – inflation, job insecurity, and skyrocketing housing costs. In this way, populists frustrated with the Democratic Party’s defense of entrenched institutions, progressives disillusioned by the party’s unwillingness to push bold economic reforms on the scale of Social Security and Medicare, and moderates weary of the unpopular demands from social movements or liberal fixation on culture and representation, are all, in different ways, diagnosing the same problem: a party that has lost its connection to the more salient forces shaping working class life.

These policy priorities must be communicated in ways that emphasize shared material benefits like universal childcare, affordable housing, Big Tech accountability, and Medicare for All - as solutions for everyone, not just elite reforms. And their tone must be fiery and populist, not sedate and technocratic, which is profoundly understood on the Right. Lilliana Mason’s research into the powerful role of tone and method of political communication of Donald Trump unpacks the cultural and political power of resentment narratives, the right wing attentional regime projecting these narratives, the racial animus behind the narratives when it comes to the argument that improving the material conditions of the working class will garner their political support.

Republican resentment narratives are simple, compelling, and emotional stories that punch down, fostering animosity and offering its adherents an explanation for their unhappiness and rage. Across races, resentment narratives have captured “low-education” voters with simple explanations of who is to blame for their diminished status and standing. Progressives need to harness the same populist energy while punching up. Democrats and progressive leaders should also regularly test whether their messaging is accessible at even an eighth-grade reading level; Trump speaks at a fourth-grade level, and his simplicity is key to his appeal.

How does the Democratic Party relate to movements?

Realignment, however, requires more than populist economic policy or savvy communication. It requires the synchronization of movements and parties, each fulfilling roles the other cannot. Movements generate political will through urgency, a social base, and disruption, while parties institutionalize change by winning elections and passing laws – frequently in tension but ultimately aligned toward shared objectives.

Movements shape public opinion in ways elections merely reflect, challenging the right’s framing and terrain while organizing around a vision of society that transcends the immediate horizon. They supply the energy, vision, and moral urgency to disrupt stagnant regimes and inspire bold change, not just by reacting to today’s conditions but by investing in a long-term theory of transformation. Parties, in turn, provide the structure and machinery to institutionalize those demands into enduring governance.

From Lincoln and abolition to FDR and labor unions to Johnson and civil rights, these partnerships didn’t merely respond to crises, they redefined what was politically possible. The tension between Lincoln’s pragmatism and Thaddeus Stevens’s radicalism reminds us that transformational change requires both ideological vision and strategic power. Without this fusion, transformative potential dissipates, leaving regimes to stagnate rather than fall. The dissonance between the Biden presidency, the Harris campaign, and social movement energy highlights the steep cost of movements and parties failing to align and craft a shared vision that resonates with the nation's mood.

The question of the composition of a coalition, the ideas that can reach and mobilize it, and how to convey those ideas are central. However, far too often, their horizon is limited to winning this or that election, one or two cycles out. If the point of realignment is to transform our politics in a more fundamental way, then we have to consider a much more multi-dimensional, longer view approach.

A few historical lessons

Realignment isn’t the work of one group or one tactic; it requires a broad ecosystem of organizations, from unions and base-building organizations to think tanks and party insiders, all moving toward a shared horizon. It demands both mass strategies that build grassroots power and elite strategies that influence decision-makers and set the terms of the debate. Realignment is also waged in a broader social and cultural context, leveraging or pushing against dominant political and economic paradigms.

Consider the transformation of the Democratic Party in the 1970s and the complex interplay between personnel, policy, and paradigms. Newly-elected Democrats of the mid-1970s realigned American politics, shedding the populist and redistributionist politics of the New Deal and Great Society, ushering in a forty-year period of neoliberalism marked by massive wealth concentration, declines in union membership, and income inequality. Yet, we’ve also seen many of these Democrats take on domestic violence, homophobia, discrimination, and civil and human rights more broadly – hard-won battles that expanded legal protections and social recognition for groups long excluded from the full promise of American democracy.

These “New Democrats” cemented the culture vs. economics poles of debate that we’re still navigating today, for better and worse. This is what we call a vector of polarization, an axis that defines debate, shapes politics, and serves as a compass point for meaning making. It also set the intellectual foundation for a generation of electeds, staffers, and power brokers who steered the Democratic Party away from its traditional power centers (labor unions, urban machines, and the civil rights movement) and toward Wall Street and Silicon Valley, laying the groundwork for Bill Clinton’s presidency and a coalition increasingly shaped by elite donors and the PMC. The cultural wars, identity politics, and wokeness debates we are steeped in today can trace their origins back at least decades.

Realignment isn’t just about reacting to voter blocs, it’s about constructing a shared political identity with boundaries defined by vectors of polarization. It forms the container that binds diverse struggles into a common cause, creating a new majority with a cohesive governing vision. Lasting transformation requires forging connections between different movements and demands – linking their interests in a way that reshapes the political landscape and establishes a new common sense. This doesn’t happen overnight; it takes coordinated strategies across multiple fronts, sustained over time.

And our current (media) reality

Progressives are beginning to draw out the implications of the attention economy for our movements and media strategies, but we’re way behind. Steve Bannon’s “Flood The Zone” strategy isn’t just misinformation, it’s volume. Trump doesn’t just seek headlines, he turns his base into millions of megaphones. Greg Abbott’s migrant busing stunt wasn’t a policy proposal, it was a political weapon designed to go viral, seize the conversation, and force Democrats into a defensive crouch. The actual policy debate – on asylum law, refugee resettlement, the border – became tangential. Abbott wasn’t trying to win a debate; he was trying to win attention.

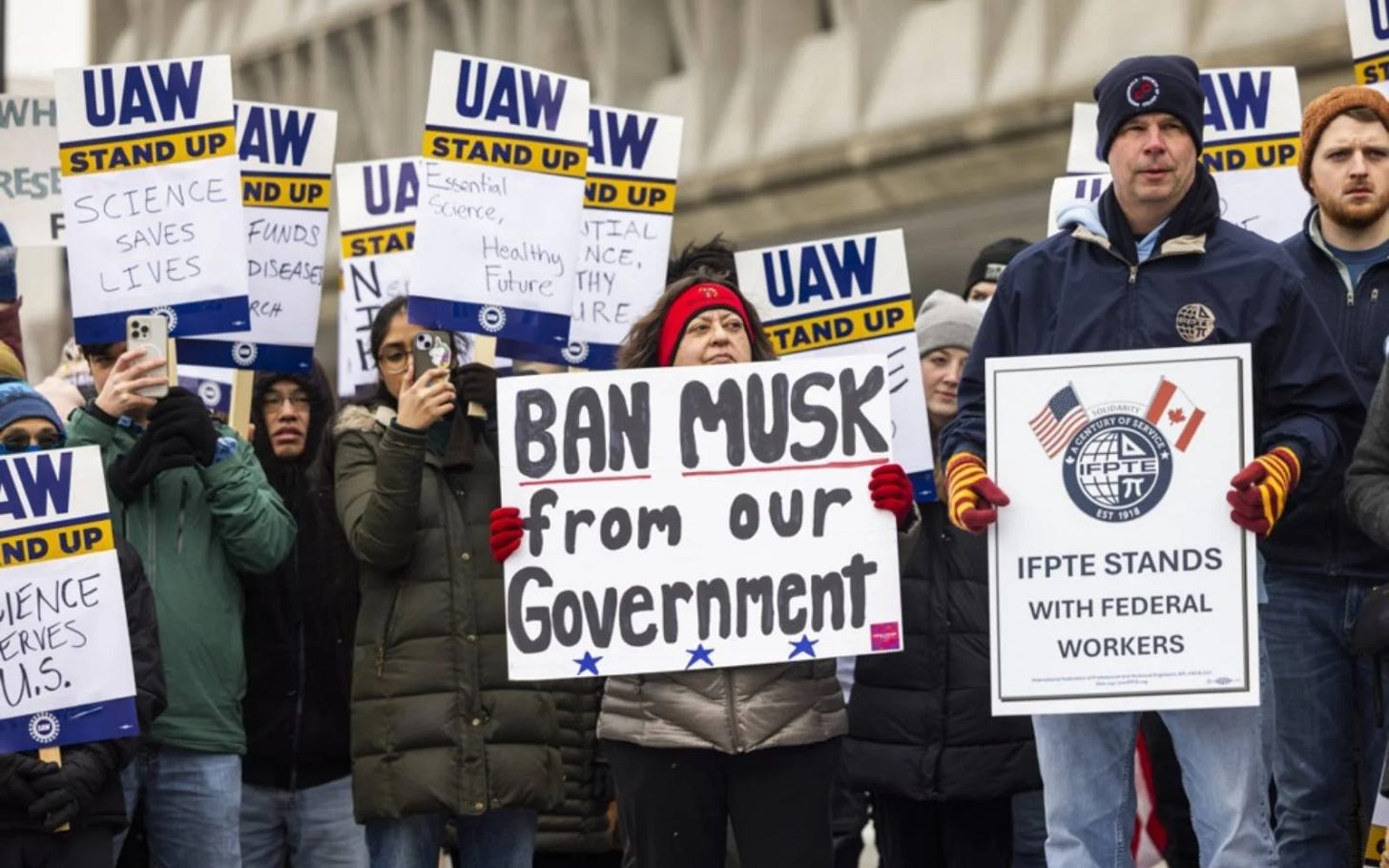

Elon Musk gets this better than anyone. Buying Twitter (now X) was never just about owning a social media company. It was about seizing the loudest bullhorn on the planet. Musk has perfected the craft of making himself the axis around which the news cycle spins, whether through performative political trolling, impulsive corporate decrees, or manufactured personal spectacle. Like Trump, he understands that in an economy where attention is the only currency that matters, the nature of that attention – adoration, outrage, incredulity – is irrelevant. It’s about keeping eyes locked on him, while progressives fixate on fine-tuning their message or corralling every group into perfect alignment.

Meanwhile, Democrats still act as if good policy sells itself. They fine-tune messaging, test slogans, and optimize for approval, assuming clarity will translate into persuasion. But persuasion requires more than the right words – it requires being heard. For a decade, progressives have prioritized wordsmithing over distribution, coordination over amplification. Meanwhile, the right floods every available channel with content, ensuring its arguments define the debate. Politics isn’t just about having the best message; it’s about owning the conversation. And in that fight, the center-left coalition is still playing by the old rules.

This media imbalance is, at its core, a structural issue. Republican elites no longer command their party, adapting to the pressures of a base radicalized by Tea Party and MAGA primary victories and an ecosystem of right-wing media outlets that shape—but don’t entirely dictate—the party’s agenda. Figures like Tucker Carlson and Ben Shapiro don’t hand down marching orders; they channel and amplify grievances already circulating within the conservative electorate, reinforcing narratives that politicians, in turn, feel compelled to heed. Republican voters, deeply distrustful of mainstream institutions, exist in a media ecosystem that validates itself and preemptively discredits establishment narratives. Unlike in the Democratic Party, where the establishment still holds power over any populist challenge , the right’s populist media ecosystem exerts real influence—not because of any single media figure, but because its most powerful product, Trump, seized control of the party itself. His rise didn’t just validate these outlets; it entrenched them as the GOP’s ideological enforcers and disseminators. Republican politicians take more cues from a feedback loop of anti-establishment voices that don’t just shape the conversation—they define the party’s brand, punishing anyone who falls out of step.

The Democratic Party, by contrast, remains more top-down, its boundaries set by politicians, think tanks, and legacy media like The New York Times and MSNBC, in turn trusted and consumed by rank and file Democratic primary voters. This means progressives can’t simply bypass elite persuasion the way conservatives can. If an idea is deemed too radical for mainstream outlets, it won’t gain traction within the Democratic ecosystem, no matter how popular it is at the grassroots level.

Progressives therefore face a dual challenge: they must both navigate institutional elites who shape what’s considered legitimate political discourse within the center-left ecosystem and build the kind of mass-distribution media infrastructure the right already has. One without the other is a dead end.

The Bloc

One of the common responses to the Manifesto was essentially “I agree with your analysis and critique, but how do we start implementing the many solutions you put forward?” Our answer, our modest but hopefully significant contribution to the goal of realignment, is The Bloc.

Over the last few months, we have been developing three interconnected strategies to address some of the needs outlined in the Populist Manifesto:

Movements: Equipping social movement organizations with strategies to be more populist and majoritarian, capable of engaging and moving a wider audience and base.

Media: Pitching and placing movement leaders into mainstream, political and new media, so that they can compete in the attention economy and break out of narrow issue-silos.

Politics: Working with electeds and their staff to influence both public opinion and political debate, addressing critical gaps in the progressive echo chamber.

The Bloc partners with base-building organizations that aren’t just mobilizing the already engaged but strive to shift the political center – making working-class struggles the foundation of a majoritarian, populist movement capable of contesting power and beating back authoritarianism. We offer intensive training, coaching, and a peer cohort to refine their ability to build majoritarian support, navigate ideological conflicts, and bridge the gap between grassroots movements and formal politics – developing the skills to engage with mainstream media, influence party dynamics, and effectively persuade broader audiences beyond their base.

Movement leaders also need support in tracking the political landscape, anticipating key narratives, and turning openings into opportunities. Through media pitching and an aggressive earned media strategy, The Bloc works to ensure our priorities shape key political debates in the venues that shift public and elite opinion. Our work with electeds is part of this strategy.

Finally, elected officials have a unique ability to set the political agenda, not to mention the outsized import of political communication in all media channels today. Opinion leaders, media, and party elites pay attention to politicians in a way they simply don’t with nonprofit executives or movement leaders. If we want to shape the political landscape, we must work with and often push those who already have power and standing within it. The Bloc is developing a political department that can channel movement energy effectively into the offices of decision makers, ensuring that elected officials are not just sympathetic to progressive demands but actively champion them.

+++

The Bloc is named for what it aims to build: a force strong enough to realign our politics and reorganize power in our society. We envision a bloc of voters demanding a new political reality, a bloc of legislators prepared to govern through it, and a bloc of movements making that shift inevitable. In short, a historic bloc.

The Populist Manifesto laid out a seven-point plan for realignment. The Bloc is an attempt to address some of those needs, and to meet the rising authoritarian threat with a strategy to build countervailing power. Our contribution is to be a strategic media partner - one that coordinates, strengthens, and scales anti-authoritarian strategy so our movements don’t just momentarily disrupt, but might, just possibly, win an era.

NB: Things are moving fast and we’re trying to keep up, and share our thinking publicly even if it’s slightly speculative and requires revision (or retraction!). In the months ahead, we’ll share our take on the deeper structural shifts reshaping movements, media, and politics. From DOGE and Elon Musk’s growing entanglements to the authoritarian surge and its backlash, the affordability crisis, and the evolving path to an anti-MAGA majority. These aren’t isolated developments. We see them as signals of a broader recalibration of state power, economic structures, and the ideological battle over our economy, democracy, and culture in the 21st century.

Inspiring message. Have you sent it to Democrats at many levels?